Government outsourcing, especially outsourcing of IT personnel, is costing Canadians billions of dollars each year. From time to time, outsourcing may be necessary to augment staff compliments or bring in external skills and expertise1. But years of unchecked spending on outsourcing has created a shadow public service of consultants operating alongside the government workforce. This shadow public service plays by an entirely different set of rules: they are not hired based on merit, representation, fairness or transparency; they are not subject to budget restraints or hiring freezes; and they are not accountable to the Canadian public2. It’s time for a major shift in outsourcing policy in the federal public service.

Over the course of 2021, PIPSC will release a series of investigative reports unpacking the government’s growing reliance on outsourcing and its true costs.

Part two: Outsourcing and gender equity

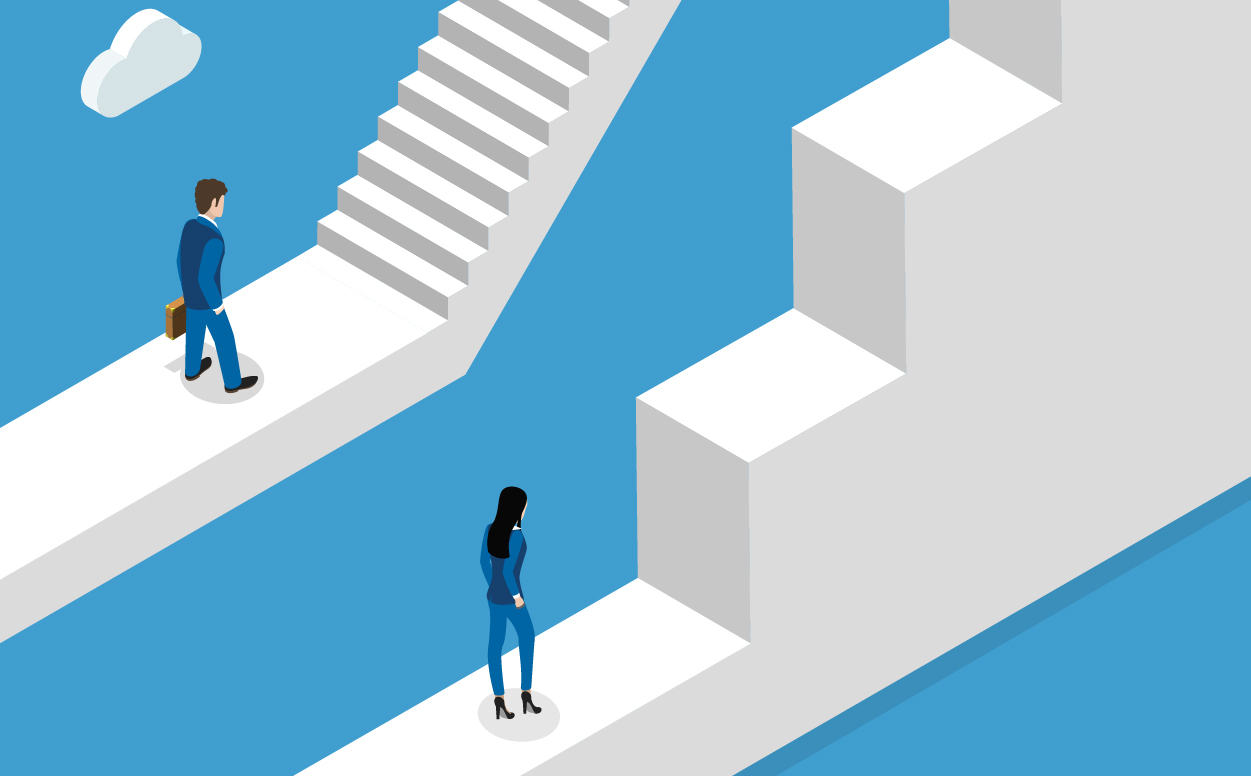

Government outsourcing deepens gender inequity across Canada's public service. In IT, lucrative contracts are doled out to a male-dominant industry that has notoriously struggled with gender equity. While at the same time, lower paid and precarious temporary service contracts are disproportionately filled by women. The majority of temporary workers become trapped in a cycle of persistent temporary work, defined by low pay, few if any fringe benefits, and high risk of unemployment and labour force exit3.

Part one: The real cost of outsourcing demonstrates that the government’s reliance on external consultants and contractors to provide services to Canadians has more than doubled since 2011. Years of unchecked outsourcing has created a shadow public service of consultants and contractors working alongside the public service. But who works in the shadow public service? This report examines the consultants and temporary workers who fill the ranks of the shadow public service. It highlights the vastly different experiences of IT consultants compared with temporary workers. It shows that outsourcing bypasses important staffing values, which in turn, drives precarious work and undermines gender equity in the public service. It explores the connections between government staffing and outsourcing while identifying ways to make staffing faster and more flexible without undermining core staffing values.

Government outsourcing isn’t only expensive and wasteful, but also fuels gender inequity in the public service.

Staffing values in Canada’s public service

The public sector is subject to legislation that actively works to build equity, diversity, and inclusion into hiring and recruitment. The Employment Equity Act (EEA) promotes equal opportunities for marginalized groups – women, Indigenous people, persons with disabilities and racialized people. The Public Service Employment Act (PSEA) promotes merit, accountability, transparency and representation based on language, region, and gender. Together this legislation aims to create a public service that represents the population it serves.

When managers rely on outsourcing as a backchannel to staffing, they bypass the values protected by the EEA and PSEA, fueling gender inequity and making the public service less representative of the Canadian public.

Who works in the shadow public service?

IT consultants, management consultants and temporary workers are the majority of the shadow public service. IT consultants make up the largest share of the shadow public service, accounting for more than 7 in 10 dollars spent on personnel outsourcing4. Similar to management consultants, IT consultants are drawn from a male-dominated industry and paid generously for their services. On the other end of the spectrum, temporary workers are often women, strung along on multiple short-term contracts and paid less than permanent staff. While temporary workers occupy a relatively small share of the shadow public service, this work has grown at a rate nearly 4 times greater than permanent staff since 20115. This demonstrates a fast growing preference for precarious work in the public service.

Who are the IT consultants?

The IT consultants working in the shadow public service are drawn mainly from the male-dominant tech workforce of the Ottawa-Gatineau region, working for tech giants like IBM, Veritaaq, or Randstad. Only about 2 out of 10 tech workers in the Ottawa-Gatineau region are women and are paid about $13,000 less per year than men. On average, members of equity-seeking groups are paid about $9,700 less6.

The pay gap between men and women in the tech sector is actually larger for workers with a bachelor’s degree or higher. The larger pay gap at higher levels of education means that women in tech with an education above a bachelor’s degree actually make less relative to their male counterparts than women with less education7.

IT consultants working with the Canadian government are likely among the top earners in Canada. While the federal government does not publish what individual IT consultants are paid on lucrative federal government contracts, IT consultants working for the government of Ontario cost about 30% more per year than a similar full-time IT worker, even after accounting for benefits8.

The largest and fastest-growing segment of the shadow public service is in a male-dominated field where women and members of equity seeking groups are paid less. Most of the work done by the IT consultants would be better done by the public service, for significantly less cost and where pay is guaranteed to be equitable9.

Who are the temporary workers?

The government’s increasing reliance on temporary workers has meant that many of these “good jobs” aren’t so good after all. Growing temporary work in the federal government has dire long-term implications for these workers.

Unlike an IT consultant, temporary workers are usually women and are paid less than comparable permanent employees. According to Statistics Canada, 56% of temporary workers in public administration are women and are paid about 21% less than permanent employees10. Women temporary workers not only have lower starting pay than men, but they also have a larger and more persistent pay gap with permanent employees over a five year period11.

Managers are increasingly turning to temporary workers as a cheap option to fill resource needs. Temporary work is cheaper because the workers do not have the same safeguards – like pay, benefits and job security – that permanent employees are guaranteed in their collective agreements. Temporary work provides additional cost savings for the government because managers are not required to invest in the career development of temporary workers as they are with permanent employees. These savings have led managers to increasingly balance their budgets on the backs of temporary workers12.

The permanence of temporary work

A common misconception about temporary workers is that they are only hired for short-term assignments. While temporary contracts are tempting for workers who see them as a foot-in-the-door to the public service, many temporary workers get trapped in ongoing precarious work within the government. For instance, the Public Service Commission of Canada found that 1 in 5 temporary work contracts were for long-term and continuous work. Only about 1 in 10 temporary workers obtained permanent positions in the public service within 180 days of their contract ending13.

A broken staffing system drives outsourcing and perpetuates inequality

The staffing system in public service is deeply connected with outsourcing. Staffing in the public service is costly, time-intensive and particularly bad at matching skills to the requirements of increasingly project-based work. Numerous hiring rules, security clearances and other bottlenecks push the average time it takes to hire a new full-time employee to 198 days (over 6 months)14.

It is no wonder that managers have little faith in the staffing system to deliver resources. Nearly 9 in 10 managers surveyed in the 2018 Staffing and Non-partisanship survey believe that staffing is burdensome while more than 6 in 10 believe it is not quick enough15. Conversely, managers interviewed by the Public Service Commission (PSC) cited “speed” and “flexibility” as the main advantages of outsourcing16.

The mismatch between fast and flexible contracting mechanisms on the one hand, and a slow and cumbersome staffing system on the other, incentivize managers to bypass staffing in favour of outsourcing.

Rethinking staffing

The federal government recognizes that its staffing system is broken. In 2018, the House of Commons Standing Committee on Government Operations and Estimates began a study to improve the federal public service hiring process17. The President of the Public Service Commission, Patrick Borbey, admitted in a hearing of the committee that the time it takes to hire new employees is “unacceptably long” which frustrates applicants, hiring managers and HR advisors. Adding, “[…] many strong candidates decide to work elsewhere and positions are not filled for long periods of time.”18

The government’s attempts to fix the staffing system to date have been mixed. In 2016, the PSC delegated much of the authority for staffing decisions to deputy heads of departments as a part of the New Direction in Staffing (NDS)19. Described by the PSC as “the most significant change to the staffing system we have seen in over ten years,” the NDS did not have the effect on staffing that the PSC had hoped. Incidentally, the most notable effect since the implementation of the NDS has been a marked increase in non-advertised appointments20. This can result in favouritism in hiring rather than recruitment based on qualifications alone.

The government also began testing a new way to deliver existing skills within the public service, in part to reduce the reliance on consultants. In 2016, the government launched the Free Agents pilot as a proof of concept for the larger, GC Talent cloud. The Free Agent pilot gives managers access to a pool of pre-vetted public servants with in-demand skills for short-term projects. The early results have been positive, with high levels of satisfaction from both workers and managers who participated in the pilot.

Learn more about the New Direction in Staffing and the GC Talent Cloud.

Despite the government recognizing that the staffing system is woefully inadequate, they have yet to connect the dots between staffing and outsourcing. The government needs to take drastic action to fix the staffing system – far beyond the 10% reduction in staffing times committed by the PSC – to begin reducing their reliance on outsourcing21. Fixing staffing in the public service is an essential part of the solution to reducing outsourcing.

Read PIPSC’s policy recommendations to ensure staffing in the public service is equal and equitable.

There is work to be done to ensure that Canada’s public service represents the diversity of Canadians and is a fair and equitable employer. Hiring more women into precarious government work is not a triumph for equity, diversity and inclusion. It is a subversion of equity, often abused as a way to cut costs. Outsourcing doesn’t just cost Canadians billions of dollars each year, it is undermining the government’s own goals of creating a fair, equitable and representative public service.

[1] According to the Treasury Board’s Outsourcing Policy (16.1.5) Managers can outsource for personnel if they need to fill in for a public servant during a temporary absence, to meet an unexpected fluctuation in workload, or to acquire special expertise not available within the public service. However, in the case of outsourcing IT work, managers,working with PIPSC CS members, must first make every reasonable effort to use existing employees or hire new indeterminate employees before outsourcing (Article 30.1 of the PIPSC CS Group collective agreement).

[2] David, McDonald. The Shadow Public Service. The Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives. 2011.

[3] Stecy-Hildebrandt, N., Fuller, S., & Burns, A. (2019). “Bad” Jobs in a “Good” Sector: Examining the Employment Outcomes of Temporary Work in the Canadian Public Sector. Work, Employment and Society, 33(4). P. 564.

[4] The federal government spent $11.9 billion on personnel outsourcing between 2011 and 2018, $8.5 billion or about 71% was spent on IT consultants.

[5] Spending on temporary help services grew by 78% between 2011 and 2018 while payroll spending on permanent staff grew by 21%.

[6] Brookfield Institute. Canada’s tech Dashboard: Diversity Compass. 2019. See: Visible Minority Pay Gap in Tech Occupations: Ottawa-Gatineau.

[7] Brookfield Institute. Who are Canada’s Tech Workers? January 2019. P. 22.

[8] Auditor General of Ontario. 2018 Annual Report. 3.14 Use of Consultants and Senior Advisors in Government. P. 619.

[9] Canadian Union of Public Employees (2011). Battle of the Wages. P. 1.

[10] Temps earned $21.8 an hour on average, compared with $27.71 an hour for permanent staff. Statistics Canada. Temporary Employment in Canada, 2018. May 14, 2019.

[11] Stecy-Hildebrandt, N., Fuller, S., & Burns, A. (2019). “Bad” Jobs in a “Good” Sector: Examining the Employment Outcomes of Temporary Work in the Canadian Public Sector. Work, Employment and Society, 33(4). p. 564.

[12] Ibid. p. 565.

[13] The Public Service Commission of Canada. Use of Temporary Help Services in Public Services Organizations: A Study by the Public Service Commission of Canada, October 2010. P. 28.

[14] House of Commons. Improving the Federal Public Hiring Process. 2019. P. 25.

[15] Public Service Commission of Canada. Staffing and Non-partisanship survey: Report on the Results for the Federal Public Service. 2018. P.6.

[16] Public Service Commission of Canada. Use of Temporary Help Services in Public Services Organizations. October 2010. P. 26.

[17] House of Commons. 2019. Improving the Federal Public Service Staffing Process.

[18] House of Commons. Standing Committee on Government Operations and Estimates. Evidence. 2018. P. 1.

[19] Government of Canada. New Direction in Staffing – Message from the Public Service Commission to all Public Servants. 2017.

[20] Ottawa Citizen. Non-advertised appointments on the rise in the public service, PSC data show. February 2019.

[21] House of Commons. Improving The Federal Public Service Hiring Process. 2019. P. 25.